News & Views

How do pupils use their phones in school?

While mobile phones are ubiquitous in society, they are controversial in schools. Some see them as a distraction, a source of cheating and bullying, a threat to student wellbeing, yet others see them as a useful tool for learning, communication and creativity.

But what do pupils actually do with their phones in school? And how do teachers feel about them?

What the surveys say...

At Teacher Tapp, we survey thousands of teachers in England every day to find out what's happening on the ground in schools. We've been asking about mobile phones since 2017 – and we've seen changes in that time.

Perhaps the most striking finding is that more and more schools are banning phones altogether: 40% of secondary schools now have a total ban on phone use by students during the school day, up from 28% in 2019. Primary schools are even more likely to ban phones, with 60% doing so.

The government seems to support this trend. In February 2021, it launched a consultation on behaviour and discipline in schools, which included a proposal to back headteachers who decided to ban mobile phones.

But does banning phone use positively impact students' behaviour and learning? And what are the trade-offs involved?

Pupils' phone use in the class

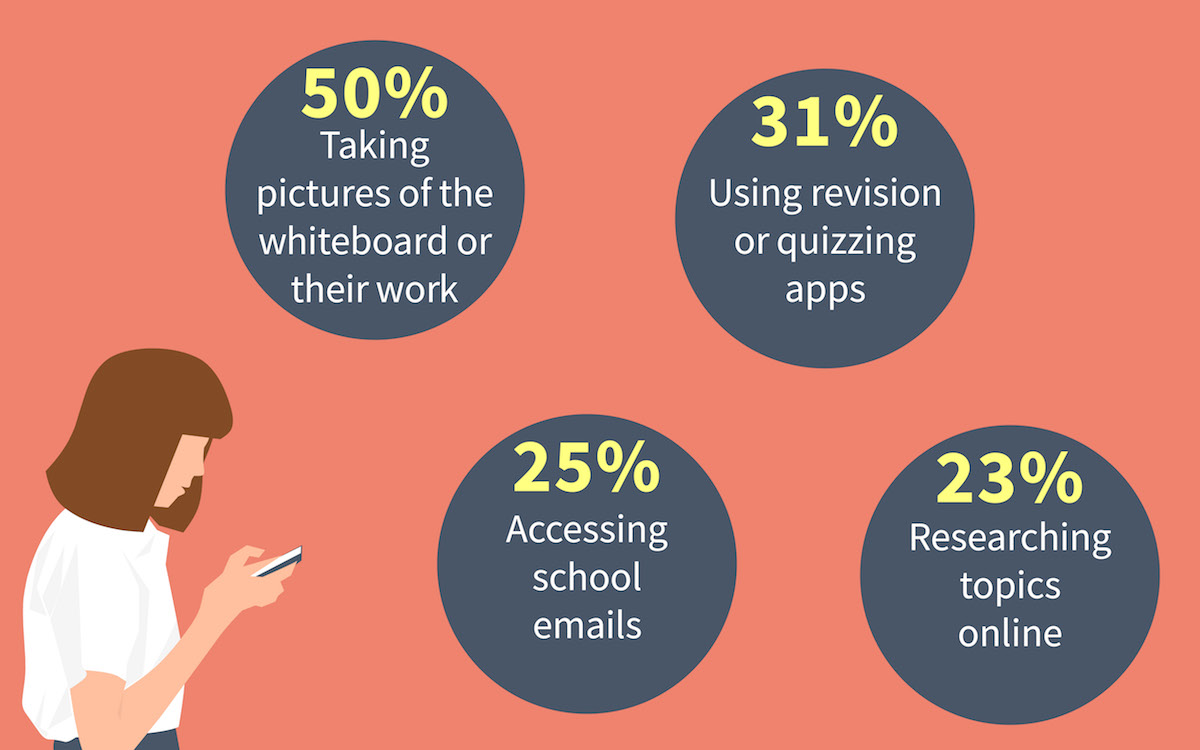

Let's look at the creative uses of phones first. Two-thirds of teachers say they let pupils use their phones at some point during the half-term when we asked. The most common uses include:

Teachers typically say that these activities can enhance students' understanding, retention and motivation, as well as foster skills such as digital literacy, creativity and collaboration.

Teachers' phone use in school

Teachers are also using their phones for professional purposes, including:

Regulating phone use in school

But while there may be reasons to use phones, there is also evidence that phone use can cause problems in the classroom. On an average day, around a third of secondary teachers deal with a student using a phone without permission, which can disrupt teaching and learning. In schools with more permissive rules around mobile phones, this increases to nearly half of the teachers, suggesting that having more controls can help reduce the disruption level. That said, even in schools with total bans on phones, on any given day, around 20% of teachers will still have to deal with a pupil using a phone inappropriately in lessons.

The tussle over what to do about confiscating phones is also exhausting for teachers, which may be why we find a difference between what teachers say they would do if a pupil has a phone on them versus what they actually do. In our surveys, we asked teachers what they would do if they were, hypothetically, to see a pupil with a phone when they shouldn't have one. Sixty-eight per cent said they would confiscate it. However, when we asked teachers who had seen a phone on a given day, only 35% actually did confiscate it.

Could this be because the hassle of having to confiscate – including a stand-off with the pupil and the difficulty of holding onto and returning the phone – is more work than simply telling the pupil to put it away? Unfortunately, if pupils know this, they are not incentivised to stop bringing their phones into school and so start chancing that they can get away with using them. For teachers, however, this is the reality of why dealing with phones becomes exhausting.

Impact on wellbeing

There is also increasing evidence that phone use can affect young people's mental health and wellbeing. A recent survey by Teacher Tapp confirmed that most teachers would like to see more regulation of social media, both for pupil wellbeing and their own. Plus, a growing number of teachers have either been a victim of or know someone who has had videos of their professional activities uploaded to video site Tik Tok without their permission which is intrusive and affects their career.

How should schools approach the issue of mobile phones? Should they ban them entirely or allow them selectively?

There is no simple answer to this question. Different schools may have different contexts, cultures and preferences. What works for one school may not work for another.

Learn about promoting digital resilience with our Pupil Resilience Award.

About the author

Laura McInerney is an education journalist, public speaker and co-founder of Teacher Tapp.