News & Views

Supporting children to get enough sleep

Sleep is important for children for numerous reasons – for physical and mental health, brain development, learning and healthy growth. Yet there is a growing understanding that many children aren’t getting enough.

It might be because they don’t have the optimal sleeping conditions available – a cool, dark room, a regular and consistent bedtime routine or even their own bed. Or perhaps their worries could be keeping them awake.

They may also be distracted by the strong lure of their mobile phone or another device. Whatever the reason, here are some tips for adults to encourage healthier sleeping habits in children.

Bedtime routines

First, it’s vital to cover the basics. Here are some simple tips:

- Ensure a regular and consistent bedtime and getting-up time. The body and brain like routine, so try to maintain regularity as far as possible.

- Advocate a calming evening, where the lights are dimmed and curtains are drawn, the air temperature is a little cooler than in the day, and there is little external stimulation on offer – except perhaps calming music or scents like lavender.

- Having a bath in the evenings can temporarily raise the body temperature which then drops a while later, promoting sleep.

- Read a story or listen to a recording of a story.

- Ensure all devices are switched off at least an hour before getting ready for bed.

- Dispel worries by writing them down or drawing them so that they are emptied from the brain.

Daytime activities that impact better sleep

Getting good sleep is not just about a decent evening experience. It’s about ensuring the rest of the day promotes better sleep too. Ensuring children are physically active enough during the day promotes better sleep: children need to be physically active for at least 60 minutes every day, ideally much more than that.

Children – in fact, all humans – need daylight, so ensure they are exposed to enough natural light. Their diet needs to be balanced, containing all the appropriate macro- and micro-nutrients. And the activities they do during the day need to be age- and stage-appropriate (for example, young children playing violent computer games might influence their ability to sleep even if they aren’t gaming just before bed).

Next, look at how constructive rest can be used throughout the day to help the body and mind relax. If a child has too much stimulation in a day, it can be difficult to get them to settle at night. Therefore, it makes sense to schedule rest breaks during the day. A short meditation or daydreaming time can help the brain and body switch off for a few minutes so that children aren’t ‘on the go’ all day. They need some downtime too.

The window of tolerance

Consider another view: that a ‘tired’ child might be tired in only one respect – their mind might have had enough but their body might still be raring to go; and vice versa – their body might be exhausted but their mind is still active. What to do then? Similarly, a child might need a different type of rest. This is where the concept of a window of tolerance (Siegel, 1999) can help. (Find out more in Dan Siegel's book The Developing Mind.)

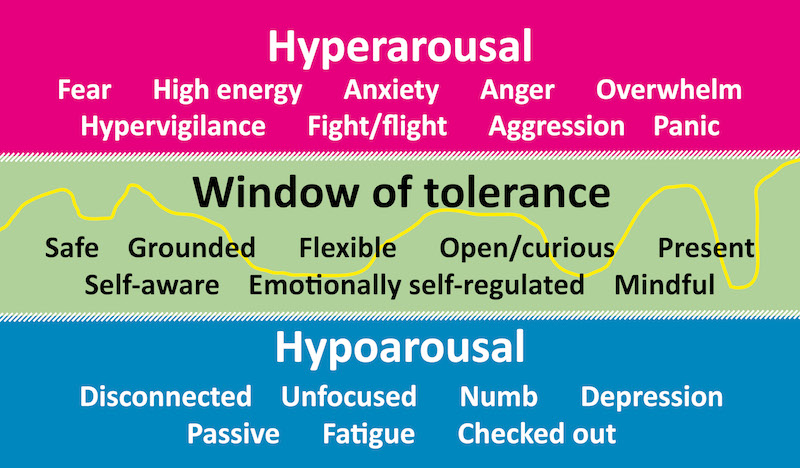

The window of tolerance is when the body and mind are in an optimal state to respond to emotions and situations; it describes the optimal amount of arousal in which a person can function effectively. Crucially, it is also when we are in our best state to learn. In this zone, a child would be present and engaged with life; they would be curious, flexible and grounded. When stressors or emotions arise, the child would be able to acknowledge them and respond to them in a meaningful way. In this state, the child is able to self-soothe and self-regulate their emotions and everyday demands.

However, if that child is outside the window of tolerance, perhaps because stressful events have pushed them outside the window, they are not in their best state. They might be in hyperarousal (where someone might feel overwhelmed, anxious or panicked) or hypoarousal (where someone might feel lethargic, numb or disconnected).

Hyperarousal or hypoarousal

As adults, our aim is to support children to recognise how they feel (when they are in hyperarousal or hypoarousal) so that they can choose which regulating practice would help them the most. In time and with practice, children will become more adept at listening to what they need and responding accordingly. Allow them the experience of both so that they can experiment and explore to find what works best for them.

It is possible for children to widen the window of tolerance by regularly calming the nervous system to regulate themselves and not just when they are in hyperarousal or hypoarousal. The more they can practise both, the more they will be better able to regulate themselves by calming their nervous systems.

Learning how to regulate

What can help when someone is outside the window of tolerance? The aim is to help the body return to a state of regulation. What you do to get there depends on which state you are in: is it hyperarousal or hypoarousal?

If a child is in hyperarousal, some exercise, dynamic movement, stretching, shaking or walking barefoot might help, as might helping them to lengthen their exhale when they focus on their breathing. They might also benefit from repetitive movements and word patterns. Conversely, if they are in hyperarousal, they need rest: lie down, breathe evenly (exhale at the same length as the inhale); listen to stories or a meditation.

As adults, we need to support children to sleep better by being prepared every single day, noticing what children need and following through with that – consistently, even when it is difficult – so that children can learn to notice and follow through for themselves.

The Pupil Wellbeing Award provides comprehensive strategies for supporting and improving physical, emotional and mental health for pupils.

About the author

Joanna Feast is an education consultant specialising in PSHE education across the age ranges. She is also the founder of Clean Wellbeing and author of the Outdoor Learning Award.