News & Views

Flexible working in schools: Addressing the retention and recruitment crisis

How much time do you give to your partner or your friends in the average week? To your parents or grandparents? If you have children, do you feel that you have more energy for other people’s children than your own? How is your work–life balance? Are you able to have a life outside of teaching?

Achieving a healthy work–life balance

This week is National Work Life Week (10–14 October). It's a national campaign spearheaded by the charity, Working Families to highlight the importance of flexible and family-friendly workplace practices.

Working Families identifies three reasons why flexible working matters:

- Parents and carers are struggling financially, especially with the cost-of-living crisis. Flexible jobs enable those who need flexibility to find and stay in paid work.

- Flexible and family-focused workplaces boost retention. Parents who were supported by their employer to work flexibly are twice as likely to remain with their employer for the next two years.

- The pandemic increased flexible working, including from home. However, working from home is not possible or the preferred choice for everyone.

Challenges in the education sector

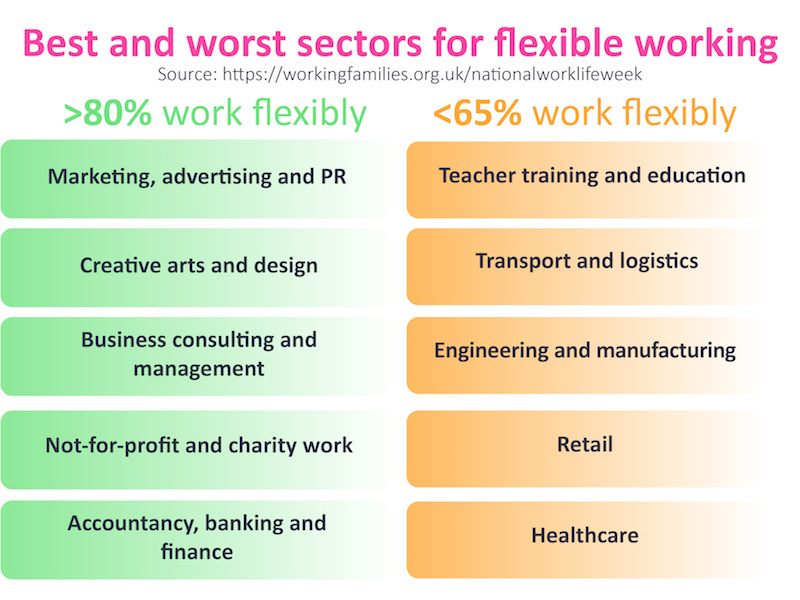

As the graphic shows, education is one of the worst sectors for flexible working. At first sight, this seems unsurprising. Teachers have to be in front of their classes. The timetable, especially in secondary schools, makes it difficult to provide continuity for pupils when they are taught by more than one teacher.

But part-time teachers are often regarded as a problem in schools, rather than a bonus. Working Families also points out that it is women who are largely in part-time roles in the workplace and who are disadvantaged when it comes to career progression.

Crisis point

Data gathered from a range of sources on teacher retention, including the DfE, illustrates an unprecedented crisis in education retention and recruitment:

• There were 6,000 fewer secondary trainees recruited this year.

• Recruitment figures missed by DfE for the ninth time in 10 years.

• There were 36,262 staff (8.1% of the total) who left the education sector, 12.4% more than in the previous year.

• For the first time, more primary teachers are leaving than secondary. Asian, black, mixed race and other ethnic minority background teachers were more likely to leave than their white counterparts.

• Only 11% of those leaving are retiring, whereas a decade ago, in 2010/11, a third of those leaving were retiring.

• The number of newly qualified teachers leaving within one year rose from 11.7% in 2020 to 12.5% in 2020/21.

• Teacher vacancies are the highest since 2010: classroom teacher vacancies were 1,368 in November 2021, up 45.5% from 2020 and almost four times higher than the 355 vacancies in 2010/11.

• Recruitment is becoming more difficult.

The message is clear: it is essential that the DfE, the government, Trusts, LAs and schools address the retention crisis and improve staff mental wellbeing. One of the ways of doing this is to adopt flexible working practices.

Five types of flexible working

In her wonderfully inspiring book, Let’s Talk About Flex, former primary headteacher and mum of three children, Emma Turner refers to five types of flexible working identified by the DfE (pp.32–36):

- Part-time working: this is doing a job for fewer hours than the full-time equivalent.

- Job-sharing: job roles and responsibilities are split between two members of staff.

- Compressed hours: a teacher works their allocated hours in fewer than five days and uses the remaining time for non-teaching tasks.

- Staggered hours: directed time is calculated when the teacher arrives at school. For example, on some days of the week, a teacher drops off their own children at daycare and reaches school 20 minutes after the start of the day.

- Working from home: while this is challenging, Turner points to the COVID-19 pandemic to illustrate that it is not impossible. If a teacher is not required to teach or supervise at the beginning or end of the day, it is better for their work–life balance to work from home.

Turner’s book draws on her own experience of flexible working throughout her diverse career and how it enabled her to achieve a better balance between her life as a parent and her work as an educator.

Other ways to work flexibly

In 2019, the DfE published a report on flexible working. In addition to Turner’s types of flexibility, it identified:

- split shifts – a working shift comprising two or more separate periods of duty in a day

- staggered weeks – such as a formal agreement to work outside term-time to deliver booster classes/sports programmes/enrichment activities

- phased retirement – gradually reduced working hours and/or responsibilities to transition from full-time to retirement

- annualised hours – working hours spread across the year, which may include some school closure days or where hours vary across the year to suit the school and employee

- sabbatical – employee takes a period away from work, over and above annual leave (usually the job is kept open for them to return)

- career break – employee takes unpaid time off work (the contract is suspended or ended, without a guaranteed return, depending on policy and individual agreement)

- flexi/lieu time – the paid time off work an employee gets for having worked additional hours

- family leave – days of authorised leave during term-time, for example, to care for family members.

Maternity and paternity leave can be combined with flexible working, easing a teacher back into the workplace and enabling parents to spend more time with their babies.

Ways to promote flexible working

While the complexity of promoting flexibility within the timetable in secondary schools is challenging, Sec Ed’s article, ‘How flexible working can succeed in your secondary school’, describes helpful strategies to pave the way:

- Ask staff if they would be willing to teach a second subject.

- Consider allowing staff to carry out some of their PPA at home.

- Hold meetings virtually.

- Staff/departmental meetings – is every meeting necessary? Is the agenda relevant to all staff? Are there other ways of giving staff information/training? Are meetings held because the calendar says so, rather than because of need?

Flexible working to achieve work–life balance is no longer a nice-to-have. It is a necessity if we are to overcome the recruitment and retention crisis. As Mike Applewhite, headteacher of William de Ferrers School in Essex puts it:

‘Our staff recognise we are working hard and putting wellbeing at the forefront. They know we listen and we’re open to dialogue about approaches such as flexible working which can help to make staff feel valued and appreciated’ (Sec Ed).

If staff don’t feel valued and appreciated, they might well leave your school. Or worse, leave the profession they once loved, forever.

Our Staff Wellbeing Award offers further ways to nurture and support the physical and mental welfare of staff in your school.

About the author

Steve Waters is a wellbeing and mental health consultant and founder/CEO of the Teach Well Toolkit. He is also the author of the Staff Wellbeing Award and Cultures of Staff Wellbeing and Mental Health in Schools.