News & Views

Stress in teaching: What it is and what you can do about it

Today is National Stress Awareness Day. It is an opportunity to reflect on our experience of stress and what we can do about it.

- ‘I’m so stressed. I’m stuck in this traffic jam and I’ll be late for my appointment.’

- ‘I went shopping on Saturday and it was heaving. When I got back home, I felt so stressed that I had an early gin and tonic!’

- ‘We nearly lost the match in the last minute. So stressful!’

Stress is part of our experience of being human. Stress can worsen existing mental health issues or lead to new ones. We frequently refer to it in our everyday conversations. When we do so, we usually mean a short-lived experience that goes away when we do something that helps us relax.

There are many definitions of stress. The World Health Organization (WHO) describes it as: ‘… any type of change that causes physical, emotional or psychological strain. Stress is your body’s response to anything that requires attention or action.'

The stress reaction

The WHO definition points to the necessity to pay ‘attention’ to our body’s response or to take ‘action’. We are familiar with the ‘fight or flight’ response. It originates in our ancestors’ reactions as cave-dwellers to danger from animals or other human beings. They could either stand and engage with their enemies or escape by running away from them. Apart from war, there are very few occasions today when we need a fight or flight response. But our bodies still behave as if we do and release the hormones adrenaline and cortisol. They speed up our heart rate, slow digestion, divert blood flow to major muscle groups and give the body a burst of energy and strength. In an athlete preparing for a race, these stress responses are helpful and increase performance. But they are potentially damaging to us if they are not in preparation for taking action and we do nothing to dissipate them.

The consequences of being stressed remain in our system and can cause physical symptoms. Over a long period, we can experience lasting damage.

Levels of stress in the teaching profession

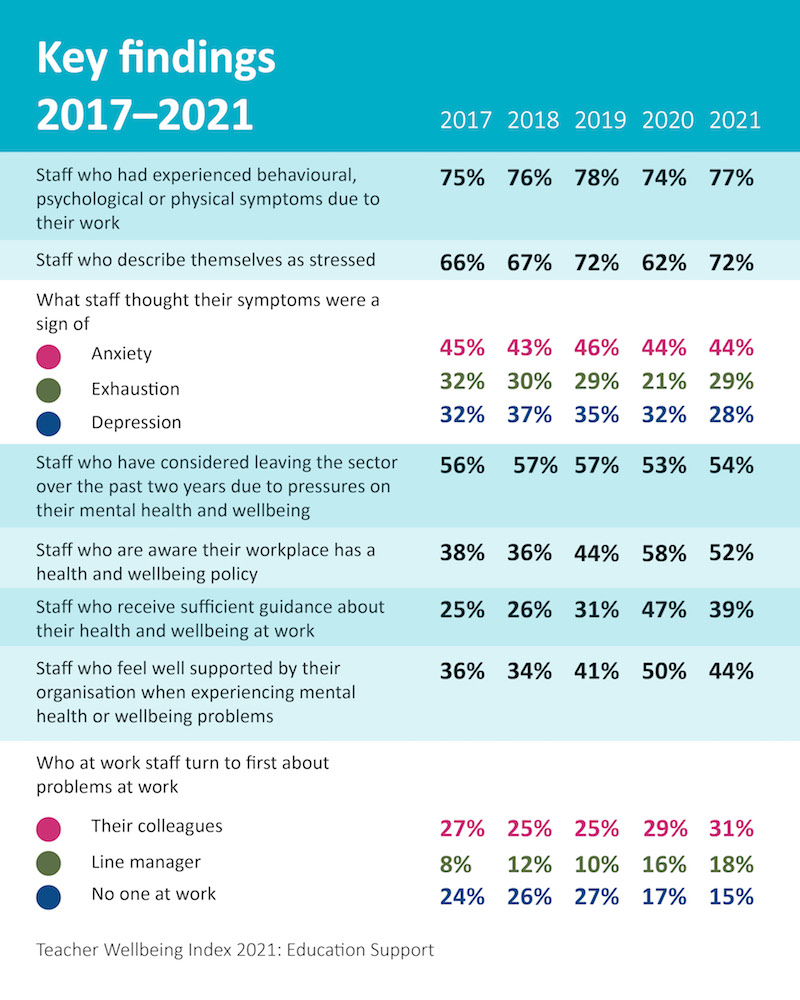

The charity Education Support publishes a Teacher Wellbeing Index report on the mental health and wellbeing of education professionals. Its most recent report in 2021 summarised its findings over the last five years. The following data is from its executive summary.

- Seventy-seven per cent of teachers experienced behavioural, psychological or physical symptoms due to their work.

- Seventy-two per cent described themselves as stressed – an alarming 10 per cent increase since 2020.

Education Support warns that: ‘Levels of stress and anxiety have remained unsustainably high [in the last five years]’ (p.12).

In her foreword, Sinead McBrearty, CEO of Education Support writes: ‘… this report is a wake-up call for anyone who cares about the future of education in the UK. Three-quarters of the workforce experience behavioural, psychological or physical symptoms of poor wellbeing due to work. Our education workforce has relatively high levels of anxiety and depression compared to the general population, and levels of exhaustion and acute stress are rising’ (p.3).

These high levels of stress have led to a crisis in retention and recruitment:

- Fifty-four per cent of teachers have thought about leaving the profession in the last year (p.9).

- Over a third of early career teachers leave within the first five years (School Workforce in England).

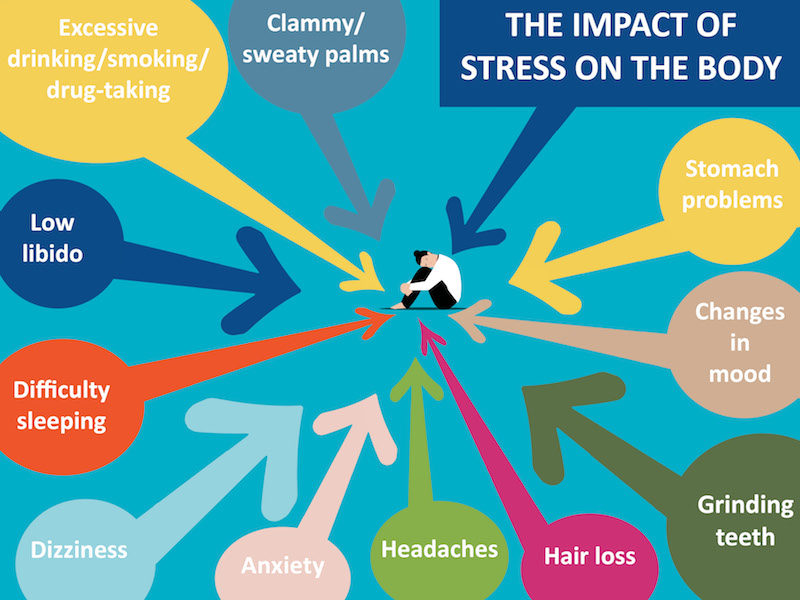

The impact of stress on the body

The following graphic demonstrates the physical effects of stress.

Long-term stress can lead to:

- high blood pressure

- weight gain/weight loss

- rapid heartbeat

- tense and laboured breathing

- chest pain

- gastrointestinal disturbance/pain

- frequent illnesses, such as colds

- hyperthyroidism

- changes in the menstrual cycle

- mouth/stomach ulcers

- tooth and gum disease.

What can you do about stress?

In a previous blog (Putting teachers in control: The importance of decision-making to staff wellbeing), I referred to a lack of control as one of the factors that can lead to burnout. If you have little control over your work at school, this will also cause stress. Although there isn't space here to discuss it, your school has a responsibility to look after your mental health by reducing workload and implementing staff wellbeing strategies. Perhaps you can get together with your colleagues and put recommendations to leadership to reduce stress?

Practical ways to reduce your stress

Identify what you can control, such as:

- Accept that you don’t have to be perfect – just ‘good enough'.

- Get up 15 minutes earlier to avoid rushing and worrying about being late.

- Restrict the extent of your marking, especially in subjects that require extended writing responses.

- Reduce caffeine intake.

- Practise mindfulness meditation or breathing exercises. Try these NHS breathing exercises for dealing with stress.

- Increase exercise. The NHS recommendation is to walk briskly for 30 minutes, five times each week but any exercise is better than none. If you prefer exercise classes or the gym, plan when you will go.

- Adjust your diet. Reduce sugar, salt and unsaturated fats in your diet. Eat more fruit. Drink more water – take a bottle of water with you everywhere in the school.

- Go out at least once a week: to the theatre, meet up with friends, shop, have a meal, attend a football match or other sporting event.

You might need medication and/or therapy to cope with sustained stress. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT), for example, which focuses on changing negative thought patterns, has been successful as a time-limited treatment for stress.

However, medical intervention will have a reduced impact if the source of the stress is not addressed. Don’t accept that high levels of long-term stress are ‘just part of the job’. When people say this, they also usually mean that nothing can be done about it. Of course, teaching is demanding, physically and mentally. But schools that take care of their staff can reduce both the degree and amount of stress they experience. They also take action to support individual members of staff when necessary, especially if they are suffering some of the physical consequences of stress.

Decide how to manage your stress

There are only three choices open to you if you are ill with stress and your school is not taking action:

- Change yourself by reducing your levels of stress.

- Change the school by persuading leadership to take action.

- Leave the school and look for a school that values its staff.

If you love being in the classroom but are thinking of leaving teaching because of the stress levels outside it, try option 3. You won’t eradicate stress altogether, but you will be able to manage it better.

Learn more about supporting staff physical and mental welfare with our Staff Wellbeing Award.

About the author

Steve Waters is a wellbeing and mental health consultant and founder/CEO of the Teach Well Toolkit. He is also the author of the Staff Wellbeing Award and Cultures of Staff Wellbeing and Mental Health in Schools (2021).