News & Views

Teaching needs over wants: Building financial resilience from tots to teenagers

The ease with which young people can spend money online in this increasingly cashless society is scary. There are so many temptations, including those led by unscrupulous companies:

- banks encouraging credit cards and loans

- gambling sites suggesting quick wins

- gaming sites

- pop-ups

- online shopping

- cryptocurrency… the list goes on.

Starting early

It’s no wonder young people find themselves in trouble with money. What’s important to know is that a person’s attitude towards money develops in their formative years. Schools can play a big part in shaping that mindset.

It is a fallacy that it’s too early to speak to children about money in nursery or reception. Research suggests that the earlier key concepts are introduced, the better. Many infant schools have adopted a clear financial literacy programme, such as the one promoted by the charity pfeg (personal finance education group) – part of Young Enterprise, including its excellence in financial education awards.

(Image by rawpixel.com)

Balancing needs over wants

Teachers introduce money through the use of pretend shops: giving children a certain amount of money and pricing up goods in the ‘shop’. As they are learning numerals 1–10 in early years, the cost of items is in £1 denominations up to £10. In this way, children begin to see the relationship between money and goods. Teachers speak to children regularly about the difference between what they need and what they want, especially in the lead-up to special events. The reading books to support these concepts are becoming more accessible and popular, such as The Giant Who Lost his Gold Coins – an adaptation of the well-known fairy tale, Jack and the Beanstalk.

Teaching pupils that living within their means is a prudent way to manage money can be developed further as they get older. Key terms such as debt, credit and saving can be introduced through a school bank. Not only does the school bank idea encourage saving but also crucial money management skills for life.

Schools are increasingly using their own ‘currency’ in the school to develop financial literacy. Pupils gain school money through a range of achievements and attributes, such as working hard or being kind. This money is credited into a school bank account and can be used to purchase small items such as an eraser or pupils can save for larger items like cuddly toys. In this way, pupils learn patience for the greater goal. The school’s collective praise for such attitudes will reinforce important life skills. The challenge lies in encouraging young people to cherish the delayed gratification of short-term and long-term savings goals, especially when there are competing forces enticing them to get instant rewards at any cost.

Spending is a good thing but...

It is important to learn how to spend. Our economy needs us to spend as well as save. This is a life lesson. Despite financial education being compulsory in secondary schools, I have yet to see a successful programme implemented in my work as a school improvement adviser.

More often than not, pupils tell me they wish PSHE lessons were more relevant. The curriculum requires careful thought and sequencing. There is a distinct knowledge base related to financial education. Pupils need to understand the vocabulary of financial literacy well. They must be taught in an age-appropriate and meaningful way.

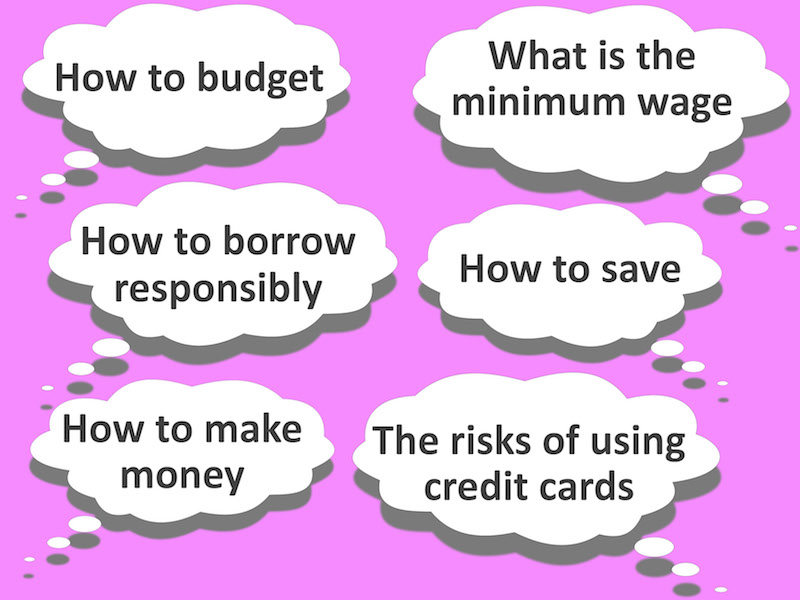

Pupils want to know:

Older students need to understand how to live on a student loan. They need to know how they will be taxed on that loan later on. Schools miss a trick when they don’t ask former students what they wished they had been taught at school. This may give some valuable insights into the current pressures, issues and concerns of young people.

For example, my son said he had to find so much out himself. YouTube has been his go-to tutor! But we all know how dangerous this can be. In fact, he revealed recently that even he had been scammed by a fake HMRC message!

Just like the academic curriculum, schools should consider ways that teachers can assess how much pupils know and understand. Often this is best done by using scenarios to which pupils can respond.

Financial literature

The literature supporting pupils’ financial literacy is increasing. However, I rarely see defined sections in school libraries for this type of reading.

Schools should consider how pupils can get interested in money matters through their regular reading routines. Martin Lewis, the founder of Moneysavingexpert.com, has donated a free textbook, Your Money Matters, which provides resources for schools to develop their financial education programme in secondary schools. How well is this being used in schools?

The post-pandemic world requires financial resilience more than ever before…

The pressure to raise the profile of financial education in schools is more pertinent than ever. There is an undisputed link between financial resilience (the ability to ride the peaks and troughs of personal and national economic cycles) and mental health in adulthood.

Children will not be immune to the post-pandemic economy of a higher cost of living and energy prices. It is incumbent upon schools to educate pupils appropriately about the importance of living within their means, recognising the difference between needs and wants, and thinking of others less fortunate than themselves.

Some schools promote second-hand sales, as part of the school’s sustainability work. Older pupils are encouraged to market their old toys, clothes and unwanted presents to make money or exchange them for something else. In this way, they learn about how to manage overconsumption but more importantly how to live within a budget.

Charities that support financial education in schools promote the idea of parents speaking to pupils openly about these pressures in families. Parents could encourage pupils to find the cheapest alternatives in the supermarket shop, or work out how much KWs are used when putting on the tumble dryer, for example. It serves two important purposes:

- It involves them in possible decision-making to manage a tight budget and thus embeds important life skills.

- It builds trust and relationships in families.

How many schools provide important guidance and tips for parents to support financial resilience?

Nine ways to enhance financial resilience

These are my tips for building a curriculum for long-term financial resilience in schools:

- Start early. Consider the literature to read to children and small-world activities in the continuous provision to promote notions of money and understanding ‘needs’ and ‘wants’.

- Develop a financial literacy section in the school library.

- Consider developing a ‘school bank’ system and using ‘school currency’.

- Build a curriculum that constructs knowledge in an age-appropriate way. Consider the necessary vocabulary and be ambitious for the pupils.

- Develop ways to assess how much pupils know and understand.

- Develop creative ways for pupils to learn to ‘live within their means’. Tackle the problem of overconsumption. Develop pupils’ understanding of people less fortunate than themselves.

- Use the experience of older pupils/alumni to shape the school’s financial education – making it more relevant and engaging.

- Engage with the charities set up to support financial education in schools.

- Consider ways to guide parents to support financial literacy and resilience.

I haven’t yet persuaded my sons that getting rich quickly by being a YouTuber or an Insta influencer is an unlikely or viable life goal! My voice, at their age, is not nearly as loud as the internet, but that is a subject for a different blog!

Discover more ways to build resilience and confidence in pupils with the Pupil Resilience Award.

Useful resources

- Young Enterprise and Young Money Resources and Tools

- Just Finance Foundation

- Barclays Life Skills Teaching Resources

- Manage Money Like A Mighty Girl: 30 Resources to Teach Kids Financial Literacy

About the author

Zarina Connolly is an independent education consultant and Ofsted lead inspector. She is also the author of Optimus Education’s Excellence in Personal Development Award.